Today’s guest post comes from author and Bristol Festival of Literature founder Jari Moate. His latest novel, Dragonfly, ventures into the territories of British Gothic and New Weird. Here he explains how he found himself harnessing these niche yet powerful genres.

Today’s guest post comes from author and Bristol Festival of Literature founder Jari Moate. His latest novel, Dragonfly, ventures into the territories of British Gothic and New Weird. Here he explains how he found himself harnessing these niche yet powerful genres.

Some writers are born to a genre, others reject it as formulaic. Some have genre thrust upon them. At its best, genre gives useful shapes and a ready-made audience.

For ages, ‘Literary Thriller’ was as far as I would go, after my first novel, Paradise Now, was tagged as such by a marketing chap at a London Book Fair depopulated by an Icelandic volcano – weird enough, already. I still think the tag is broadly right, though.

When fellow Tangent author Mike Manson told me that my novel Dragonfly was ‘the New Weird,’ I was puzzled at first, but I quickly took it, like a coat I’d been wearing suddenly had pockets where I needed them. Into those pockets I’ve since added ‘British Gothic’ and it feels like I can finally leave the house with somewhere to keep all my kit!

When fellow Tangent author Mike Manson told me that my novel Dragonfly was ‘the New Weird,’ I was puzzled at first, but I quickly took it, like a coat I’d been wearing suddenly had pockets where I needed them. Into those pockets I’ve since added ‘British Gothic’ and it feels like I can finally leave the house with somewhere to keep all my kit!

But why did it feel this way? And what is the New Weird? Isn’t it just a bit… weird? And what’s all this talk of ‘British’ Gothic?

So this is my very rough and ready, personal take on it.

Reorder the world

Have you ever woken from a nightmare, feeling scared to your bones but also renewed, refreshed even, as if the world has been ever so slightly reordered? The deck reshuffled? That, in essence, is the New Weird.

Examples of the genre include the work of China Miéville, beginning with Perdido Street Station and its mind-consuming moths, or his City And The City dramatised for TV in 2018 with its invisible wall no one must breach. Or David Mitchell’s The Bone Clocks and its creepy harvesters. Or consider Neil Gaiman.

Some describe it as alt-reality or horror-related, eschewing happy or moral endings, although I’d argue its authors have profound morality.

For me, although I don’t write fully inside the genre, it’s about the freedom to express ideas. So if I say in Dragonfly that a derelict building is coming alive, then I really do want you to tingle with the thought that I mean it, those bricks have swallowed us, or if parrots fly out of derelict ground, it serves a purpose in the story where you, and I, have joined forces to discover something truer than by simply avoiding what ‘couldn’t happen’.

At the very least, it’s a form of playfulness – a reshuffling of the cards. And it feels different from Magical Realism because of its implied threat, or spiritual jeopardy.

Disobey all limits

My writing is often about disobedience – not just about breaking a few taboos, but something harder.

In Dragonfly, a working man, a soldier known only as Marine P, returns from a war that’s propped up a world in which the suffering he witnesses – and causes – is crushing him. He can’t see how to disobey it but he knows that he must. He fails, at first, as he tragically obeys orders, wrecking his love-life and running aground on protest politics until he’s homeless and out of his mind.

But then his quest really begins, in a monstrous building with a cook who burns water, a lost map-maker, a heretic chaplain and a fake-tan villain whose sidekick dresses as Red-Nosed Rudolph… The pack is dealt for disobedience – against what people say is possible in life.

We all have times when we want to disobey the limits placed upon us, but how could my traumatised Marine P do this? Exploring this meant taking Dragonfly, beyond Realism. Within its military and political themes there had to be a grounding in some ‘facts’ but it’s not a documentary. It’s a metaphor.

“Humankind cannot bear very much reality,” said TS Elliott – so we’ll have a beer, watch the Great British Bake Off, bury ourselves in spreadsheets and bedsheets… or in a book that bends ‘reality’.

Adding my themes of love, addiction, madness and faith, I also needed Coleridge’s “suspension of disbelief” to hang from the ceiling by its fingernails – while trying not to lose the reader, nor, indeed, the plot. Weird indeed.

Make sure it rings true

All fiction is unreal. But it has to ring true. The fiction I enjoy most gets beneath the skin of life, into its soul, where we may find alarming and alluring shapes. The New Weird tag allows me to bend those shapes as far as they want to go. What decent writing must never do, though, is make those shapes feel untrue.

At times it hatches angels, at times monsters, and truest of all are the angel-monsters.

Which leads us to British Gothic. There are good reasons for a culture to bounce away from demons, mythical settings and so on. But what can result is a version of art using only the verifiable, as if fiction can ‘colour in’ what we might call the priestly religion of our times: the scientific method. But fiction refuses to be governed by those priests. As, I think, does the human soul.

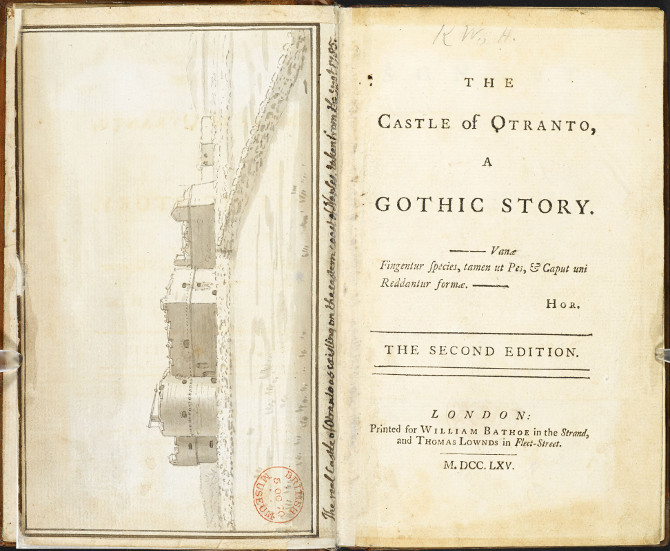

Horace Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto 1764 was the first novel to call itself “Gothic” pitching “imagination and improbability” against “a strict adherence to common life,” he said, summoning his ghosts from Shakespeare.

For me, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is the sharper attack, electrifying British readers against scientific hubris, ensuring the Gothic steamed into the mechanised scientism of the industrial age, its ghostly tales piling up, taking a leisured-class trip with Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland before its apotheosis in Dracula by Bram Stoker.

For me, Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is the sharper attack, electrifying British readers against scientific hubris, ensuring the Gothic steamed into the mechanised scientism of the industrial age, its ghostly tales piling up, taking a leisured-class trip with Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland before its apotheosis in Dracula by Bram Stoker.

After the real horrors of two World Wars, it feels quiet until Tolkien and non-Narnia CS Lewis refuel it, flying into the Transatlantic jet age with rediscovered Lovecraft, even Vonnegut and Burgess, cruising into Stephen King’s haunted hoovers and now Sarah Perry’s The Essex Serpent, or the masterful Beast by Paul Kingsnorth.

What’s ‘British’ about the Gothic is its rootedness in shadows that need no translation to its natives, but which like the Queen or Chicken Tikka Masala, may need justification to others.

Embrace the Absurd

Talking of others, the Absurd has its impact. Borges, Calvino, Ionesco or Albert Camus spring to mind, especially La Peste: in a merciless universe, a doctor is unable to save a child in a city of rats flanked by a beast – the sea. French Gothic?

In Arto Paasilinna’s The Howling Miller, industrialism sparks absurdity in darkest Finland. Forest Gothic? It certainly disobeys.

When the science-priests seem unable to explain our souls to us, in our age of encircling tech and algorithms it feels ok to explore New Weird-leaning representations of who and where we are. Even Crime gets more fantastical, dipping its toe again in the mystery, Nosferatu-like. And Gothic gains energy as Andrew Michael Hurley’s The Loney steps out of a niche imprint to stand in the English mudflats abandoned by technology, calling to us to be bone-scared of all our absolutism, pagan and otherwise, while winning polite book awards.

If some disobedience is healthy, then perhaps allow the ghosts to step beyond the machine, to speculate and thrill, in new and weird revelations of the flesh beneath. And to ring true.

About the author

About the author

Bristol writer and founder of Bristol Festival of Literature, Jari Moate has been a finance worker, folk musician, soldier in Finland, an arranger of investment into buildings that create social good and, in his own words, “always a writer”. Previous work includes Paradise Now and stories such as This Brick In My Hand, published by various independent presses. His latest novel, Dragonfly, is available from Tangent Books.

Author pic by by Paul Bullivant.

Got some writing insights to share? I’m always happy to receive feature pitches on writing genres and writing tools. Send an email to JudyDarley(at)iCloud.com.