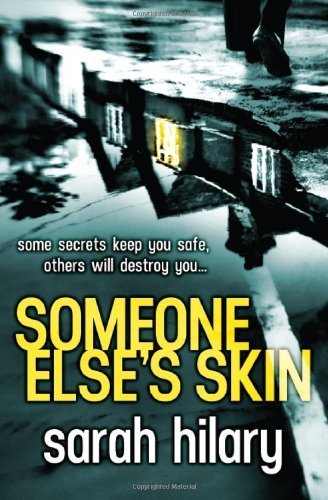

With her debut novel Someone Else’s Skin, Sarah Hilary has revealed a skill for creating characters you can really believe in. Here she shares her tip for the craft of inventing people.

With her debut novel Someone Else’s Skin, Sarah Hilary has revealed a skill for creating characters you can really believe in. Here she shares her tip for the craft of inventing people.

Source the initial glimmers

I wait for the voice to come first. I’m with Val McDermid on this: we don’t choose our characters, they choose us. Very occasionally I’ll glimpse something in a character in a TV show, or (more rarely) in real life, which will give me the beginnings of an idea, but more usually it starts with a line of dialogue, or inner monologue.

With Marnie Rome, I wrote her first, then retro-fitted the research and fine-tuning. It was more important that she felt real to the reader than real as a police detective. But I did read a lot of first person CSI-type pieces to get a feel for how she might approach her work.

Listen to your character

Listen to your character

I don’t consciously devise patterns of speech. It’s character driven, always. Marnie tends to speak quite abruptly and plainly, because she doesn’t have a lot of time or patience for double-speak. But, at the same time, she can be very empathetic, especially to victims. I love writing dialogue, but I tend to do it instinctively; it’s the one part of my craft I’ve never really had to work at.

Get to know all the sides of your character

In my first drafts, Marnie tends to be angrier and tougher. She’s often on the defensive, physically and emotionally. I find I need to dig beneath that angry surface to find the layers of response needed for the reader sees her vulnerability as well as her strength, her compassion as well her determination.

Her traumatic backstory is an important part of who she is, as it drives the narrative arc of the series. Not just what she went through, but how she has coped with it in the past (by burying herself in work) and how she will cope with it in the future (by confronting what happened and what it did to her). It’s a classic rites of passage, in some ways, but it’s complicated because it’s not just Marnie’s journey. It’s Stephen’s, her foster brother’s, too. He’s both the cause of the trauma, and its potential resolution. One way or another, he’s going to lead the pair of them into new territory.

Seek out telling details (such as Marnie’s tattoos)

The tattoos are indelible proof of Marnie’s teenage rebellion, a thing that haunts her throughout the series. Few people have seen the tattoos, which is one of the reasons she acquired them (casual sex is not an option when you have writing all over intimate parts of your body). Stephen has seen the tattoos. Marnie is still learning exactly what that means.

Choose your supporting characters with care

Characters such as Noah, Ed and Stephen each bring out a different side to Marnie. Ed is the one with the hardest task, I think, as he’s trying to help her recover at the same time as respecting her privacy at the same time as being in love with her and wanting to make her happy. That’s a tough, tough gig. Noah is a little in awe of Marnie as his boss, and as an ace DI, but he’s earning her trust, which is good for both of them. Her relationship with Stephen is the most complex one, and it’s the one which will change the most over the course of the series.

In some ways, she’s at her most vulnerable when she’s with Stephen, because he has the power to keep hurting her, by reminding her of what he did and withholding the reason why he did it. Marnie knows she will be hurt, every time she goes to see him. His punishment (long-term incarceration) is her punishment, in that sense.

Likewise, for your periphery characters

For Marnie Rome, these are the women from the refuge, especially Ayana, Hope and Simone. Ed tells Marnie that these women are ‘not her kind of victim’. They ran, and hid. They had to. But Marnie comes to see the strength in the women, different in each one, and I think that helps her to put her own strength (and weakness) into perspective.

Use your settings to explore aspects of your character

In Someone Else’s Skin, the prison and the refuge are both essential for that: enclosed spaces where it’s hard to breathe, and harder to feel safe. It was interesting, also, to put Marnie into Hope’s ‘perfect home’ with its showroom furniture and its shiny surfaces, and to watch her reactions. And Ed’s flat, with its jumble of stuff and its comfy mess. Setting is great. London is an amazing backdrop to the series, and I’m looking forward to taking Marnie into Battersea Power Station in book three.

Relish the luxury of a recurring character

I found that with Marnie Rome, it gave me the great luxury of being able to uncover her secrets slowly. She’s still surprising me, which is great, as it means she’s surprising readers too.

Create compelling, believable characters

Set goals for your characters, and then put obstacles in the way of those goals. See how your characters react, physically and emotionally. Give them at least five senses, and show them experiencing the world through those senses (i.e. not just rely on dialogue and inner monologue; tell us how the world looks, sounds, smells, feels to them). Get right inside their head, and under their skin, so the reader is right there, too. Even the nasty characters. Never show your hand as the author; instead, wrap your readers up in the story and the cast, as if it’s happening to them and/or to people they know and care about. Make them wonder what happens to the characters even after they’ve stopped reading. That’s the holy grail.

About the author

About the author

Sarah Hilary lives in Bath with her husband and daughter, where she writes quirky copy for a well-loved travel publisher. She’s also worked as a bookseller, and with the Royal Navy. An award-winning short story writer, Sarah won the Cheshire Prize for Literature in 2012. SOMEONE ELSE’S SKIN is her first novel, published by Headline in the UK, Penguin in the US, and in six other countries worldwide. A second book in the series will be published in 2015. Set in London, the books feature Detective Inspector Marnie Rome, a woman with a tragic past and a unique insight into domestic violence.

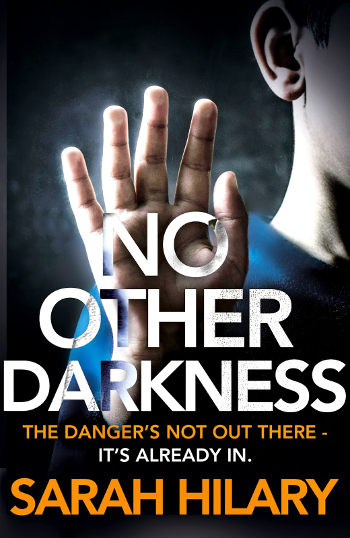

NO OTHER DARKNESS, the second Marnie Rome book, will be published in spring 2015. Sarah is currently working on the third and fourth books in the series. Follow Sarah on Twitter at @Sarah_Hilary

If you’ve read Someone Else’s Skin, Sarah Hilary’s stunning debut, you’ll have high expectations of the second book in her Marnie Rome series.

If you’ve read Someone Else’s Skin, Sarah Hilary’s stunning debut, you’ll have high expectations of the second book in her Marnie Rome series.