Award-winning short story writer Harriet Kline tells us how and why she likes to use animals as metaphors in her fiction, but warns us that they sometimes they take on a life of their own.

Award-winning short story writer Harriet Kline tells us how and why she likes to use animals as metaphors in her fiction, but warns us that they sometimes they take on a life of their own.

I talk a lot to my cat. I ask her if she’s having a lovely sleep, or if she knows how beautiful she is. I talk to other animals too. I’ve been known to greet butterflies, thank blackbirds for their songs, hurl insults at flies. Trees, recalcitrant computers, zippers also get comments aimed their way. I know I’m not the only one. Plenty of people name their cars and tell hamsters not be scared when they lift them out of the cage. Once I heard a woman say to her dog, we’ve talked about this before.

For me, there’s a particular set of feelings that comes with addressing things that won’t reply: A sense of power perhaps, in knowing that my comments will not be contradicted. A sense of foolishness, especially if I’m overheard. And also a sense of creativity. There really is no significance in a fly buzzing at my window or a zip sticking on my favourite dress, but when I speak to these things I fill them up with meaning. I create a relationship with them, through my words. We all do. We gain a sense of ourselves, of where we are in the world by relating to the things around us.

This set of feelings also occurs when I’m writing short stories. I feel powerful, creative and foolish all at once. I believe the link is that as I create a narrative, I simultaneously fill it up with meaning. As the story unfolds, the deeper, metaphorical layer is revealed. So a story about a young woman who finds a ladybird caught in her blouse is really about how she finds a small but gritty determination to survive. A story where three siblings neglect their guinea pigs is really about their unwillingness to admit to any vulnerability in themselves.

How it feels to use metaphors in your writing

What really interests me is not simply that I use metaphor as a writer, (many of us do,) but what it actually feels like to do that. I am intrigued by the very moment when something becomes significant. That twinge of self consciousness when I catch myself in the act of appropriating meaning. The pause between addressing the animal and remembering that it definitely won’t reply.

It is this active interface with metaphor, that I wanted to examine in Familiars, my collection of short stories. I wanted to make that moment of self consciousness central to each narrative and explore its effects on a range of protagonists. In some stories the significant animal relationship allows a transformation: A young woman comparing a dog’s whining with her own, comes to accept her feelings of grief.

In others the protagonist resists the moment, refusing to see significance when it is clearly present: A teenage boy is horrified by his sister’s attempts to imbue a robot with character. He insists it can have no feelings because he would rather not to admit to his own. In some stories the moment is fleeting: A woman, unable to express herself honestly is struck by the hideous hawing of a donkey. In others it is stretched into something magical: A mother struggling with feelings of awkwardness transforms repeatedly into a hare.

I chose animals (and a few magically animated objects) for this exploration because I’m certain that the impulse to talk to animals is almost universal. I guessed that the interface between animal, human and meaning is something my readers would recognise. I also suspected that many of us have imagined how the animals might reply.

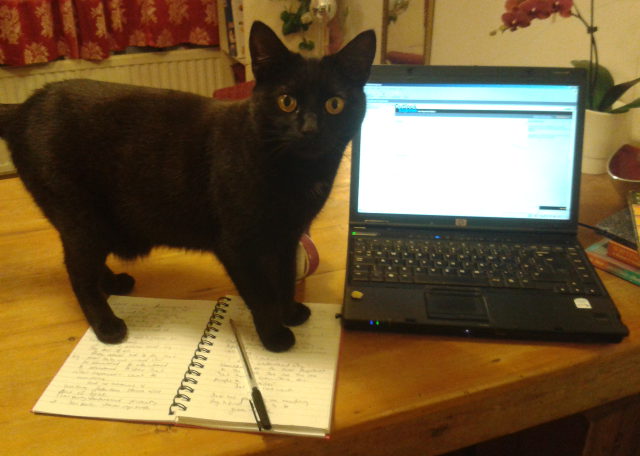

And it was here that I had the most fun with my writing. What would a cat say if it could speak its mind? How does a ghost dog feel when someone walks through it? I thought it would be difficult to put language into the minds of animals, but what I’ve learned through writing Familiars is that is even more difficult not to. When the cat walks across my notebook as I write, I can’t help imagining her thoughts: Hey, don’t look at the paper, look at me. Or when my friend’s dog brings me a ragged slipper in his jaws it’s impossible not to believe he’s thinking, love me, love me, go on, please. So it was almost a relief to give free rein to this impulse, and create whole narratives from the minds of animals. It was as if the metaphors I had chosen began to take on a life of their own.

And yet, I also wanted to show that this impulse to make meaning is really a human concern. It’s how we connect, how we love and learn, take our place in the world. So I decided that my talking cat would have no reverence for language and less for any moments of significance. Despite her abilities her priorities would still be the food bowl and a warm place to lie in the sun. And by doing this, I hope I was also able to suggest that for humans it is different. Language gives us a richer and more wonderful life. We thrive on stories and metaphors and I believe they are central to our humanity.

Harriet Kline won the London Magazine Short Story Competition 2013 and the Hissac Short Story Competition 2012. She was highly commended in the Manchester Fiction Prize 2014 and has been shortlisted and longlisted elsewhere. Two of her short stories have been broadcast on BBC Radio 4. Familiars as a collection is as yet unpublished. You can read Ghost at www.hissac.co.uk/Ghost and and Donkeys at shortstorysunday.com. Chest of Drawers appears in The London Magazine April/May 2014. Hares appears in Story.Book, Unbound Press and Spilling Ink Review. If you are interested in reading any of the other stories, contact Harriet through her website www.harrietkline.com “and we may be able to come to an arrangement.”