Writers are often advised to write what they know. Over time this has become prescriptive: write only what you know. If you are a white, middle-aged man, you can write only from the perspective of a white, middle-aged man.

Writers are often advised to write what they know. Over time this has become prescriptive: write only what you know. If you are a white, middle-aged man, you can write only from the perspective of a white, middle-aged man.

And yet it’s as reading that we gain access to the interiors of other people’s lived experiences. Why shouldn’t the same be true of writing? After all, isn’t a good imagination one of the key qualifiers for becoming a writer?

Often this requires sufficient research to make our portrayal as honest and respectful as possible. Occasionally it warrants immense leaps of creativity to invent and evoke an experience, and carry our readers along with us for the ride. Surely, our raison d’être is to lead the way on flights of fancy!

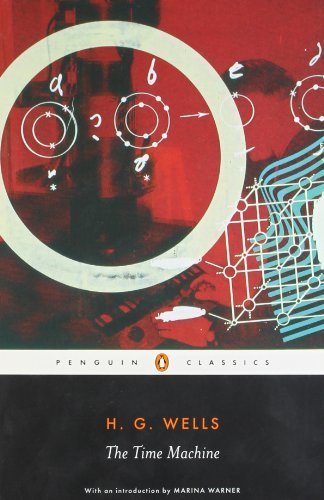

H.G. Wells achieved this with ease when he needed to supplement his income as a freelance journalist by writing and selling fiction (now, there’s a flight of fancy!) in 1895.

Ricocheting from an idea already being debated by students at the Royal College of Science that Time represented a fourth dimension, Wells published The Time Machine in 1895. After a rather ponderous start, this novella powers into a dizzy story that seems to draw from impressions of sea-sicknesses, fevered dreams and inebriation.

“The night came like the turning out of a lamp, and in another moment came tomorrow. The laboratory grew faint and hazy, then fainter and ever fainter. Tomorrow night came black, then day again, night again, day again, faster and faster still. An eddying murmur filled my ears, and a strange, dumb confusedness descended on my mind.”

Wells goes on to claim, “I am afraid I cannot convey the peculiar sensations of time travelling”, yet then describes the experience with filmic vibrancy. “They are excessively unpleasant. There is a feeling exactly like that one has upon a switchback—of a helpless headlong motion! I felt the same horrible anticipation, too, of an imminent smash. As I put on pace, night followed day like the flapping of a black wing. The dim suggestion of the laboratory seemed presently to fall away from me, and I saw the sun hopping swiftly across the sky, leaping it every minute, and every minute marking a day. I supposed the laboratory had been destroyed and I had come into the open air. I had a dim impression of scaffolding, but I was already going too fast to be conscious of any moving things. The slowest snail that ever crawled dashed by too fast for me. The twinkling succession of darkness and light was excessively painful to the eye. Then, in the intermittent darknesses, I saw the moon spinning swiftly through her quarters from new to full, and had a faint glimpse of the circling stars. Presently, as I went on, still gaining velocity, the palpitation of night and day merged into one continuous greyness; the sky took on a wonderful deepness of blue, a splendid luminous colour like that of early twilight; the jerking sun became a streak of fire, a brilliant arch, in space; the moon a fainter fluctuating band; and I could see nothing of the stars, save now and then a brighter circle flickering in the blue.”

Wells then embeds the uncanny occurrence in firm foundations by painting a scene most of us are familiar with, and adding in the relentless sense of time racing.

“The landscape was misty and vague. I was still on the hillside upon which this house now stands, and the shoulder rose above me grey and dim. I saw trees growing and changing like puffs of vapour, now brown, now green; they grew, spread, shivered, and passed away. I saw huge buildings rise up faint and fair, and pass like dreams. The whole surface of the earth seemed changed—melting and flowing under my eyes. The little hands upon the dials that registered my speed raced round faster and faster. Presently I noted that the sun belt swayed up and down, from solstice to solstice, in a minute or less, and that consequently my pace was over a year a minute; and minute by minute the white snow flashed across the world, and vanished, and was followed by the bright, brief green of spring.”

Lastly, he returns us to the bodily symptoms, or side effects, his time traveller endures. “The unpleasant sensations of the start were less poignant now. They merged at last into a kind of hysterical exhilaration. I remarked indeed a clumsy swaying of the machine, for which I was unable to account. But my mind was too confused to attend to it, so with a kind of madness growing upon me, I flung myself into futurity. At first I scarce thought of stopping, scarce thought of anything but these new sensations.”

In only two pages, Wells has created a convincing account of an imagined experience, and succeeded in making the incredible utterly plausible.

Bravo.

Read other writing masterclasses in the SkyLightRain Writing Insights series.

What are you reading? Consumed by a particular scene? I’m always happy to receive reviews and comments on books, art, theatre and film. As well as writing insights feature pitches. Send an email to JudyDarley(at)iCloud.com.