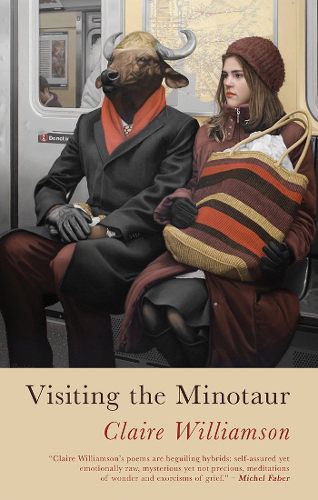

Drawing on myths to make sense of our mortality, Claire Williamson’s first collection with Seren is at once heartbreaking and comfortingly human, with the skill to make your spirits soar.

Drawing on myths to make sense of our mortality, Claire Williamson’s first collection with Seren is at once heartbreaking and comfortingly human, with the skill to make your spirits soar.

Seen through Williamson’s eyes, a half bull, half man hybrid is nothing compared to the complexities of surviving your average childhood. From the aching tenderness with which she knits memories about her own daughters to the grief and confusion of losing a sibling and mother, Williamson immerses you with such conviction that you can’t help but empathise.

There’s a distinct irreality to much of the carefully conjured imagery, which only serves to heighten the stark honesty of the sensations being shared. Family members long gone return as horses: “She thrusts her black muzzle/ into the cleft of my torso and arm/ and I feel her warmth for the first time/ since she drank that poison.”

Bereavement is a theme throughout, but even in the bleakest contemplations, Williamson manages to find humour in the moments she captures.