Today’s guest post comes from writer KM Elkes and offers an insight into the art of stringing a short story collection together.

Today’s guest post comes from writer KM Elkes and offers an insight into the art of stringing a short story collection together.

Telling people you are working on a novel is easy enough. People ‘get’ novels. Even the least reader-ish person has probably read a couple, either because they were forced to at school or because they were part of Generation Harry Potter.

But a short story collection? Not so much.

Maybe that’s because short story collections are relatively unfamiliar – not so surprising when you consider bookshops force readers into an Indiana Jones-style quest to find them. They lurk unassumingly, a diaspora spread among distant bookcases, waiting for the day when someone has the bright idea to give them a shelf of their own.

But there’s a deeper issue too – even those in the biz, writers and publishers, are sometimes ignorant of what a short story collection really is. Which makes putting one together feel like a Sisyphean task.

Think about it. There’s plenty of advice out there on what makes a good novel – how to write it, pace it, plot it, sell it. But I’ve yet to Google a go-to guide on what constitutes a fantastic collection.

Most short story writers are busy just trying to make each story the best we can. The emotional investment is quick, deep and hard, the art tricky. It’s only when you come to the point of putting your own collection together that you realise it’s not simply a matter of polishing up your bestest, nicest stories and pressing Send.

What does a short story collection involve? What does it need?

Well, in my opinion, many of the same things that characterise a good short story – unity of purpose and theme.

I’m not talking specifically about some clunky link (hey, watchya know, they’re all characters from the same street!) but something less obvious, spider silk thin at times, but there, somehow.

Look at some wonderful collections – Alice Munro’s Runaway; Cathedral by Raymond Carver; Nathan Englander’s For The Relief of Unbearable Urges; Walk the Blue Fields by Claire Keegan. Whether or not the author planned it, there is a thread that runs through these books, located in place, or in an overarching theme, in the kind of lives they tackle and in that most intangible thing: voice.

Look at some wonderful collections – Alice Munro’s Runaway; Cathedral by Raymond Carver; Nathan Englander’s For The Relief of Unbearable Urges; Walk the Blue Fields by Claire Keegan. Whether or not the author planned it, there is a thread that runs through these books, located in place, or in an overarching theme, in the kind of lives they tackle and in that most intangible thing: voice.

Regardless of point of view, tense, sympathetic or abhorrent characters, regardless of timeframe or timeline, great authors have a voice, a way of storytelling that leaves an imprint on their collection.

Think of George Saunders at the frayed edge of satire, or the rich gravy of Saul Bellow’s language, the wry humour of Kevin Barry and Edith Pearlman’s precise concision – all give a shape that is the author’s own.

What can those of us putting our debut collection learn from this?

Being ruthless is necessary, especially with our earlier work. Yes they might have won prizes or been shortlisted for decent competitions, but do these stories fit with our latest work, where a more individual voice is starting to form? Perhaps it’s time for that tricky chat: “Thanks guys, we had fun, but I’ve moved on. It’s not you, it’s me.”

Tough love is also needed for the stories that are up to scratch, but simply don’t fit in. That cracking three thousand worder, which someone said reminded them of Jorge Luis Borges, probably won’t fit if you are building a reputation as the Cheever of Milton Keynes.

Even then, this process throws up fresh dilemmas. How do you know when you’re done? How do you know that the next story you write won’t be the one to top out the collection, the crowning glory that will pull it all together?

This is particularly tricky for me, and, I suspect, many other short story writers because I don’t (I can’t) write with a collection in mind. Story writing for me is a weird alchemy, when character, voice, theme and tone come together through some process that has little to do with the analytical part of my brain.

So time is important, to allow things to accrete. Maybe the key to creating a short story collection is the key to all writing – keep going, get better at it, read stories by people who are better than you, learn from them, accept your failures, don’t get carried away with your successes, rinse and repeat.

Eventually you may begin to ‘feel’ a group of stories huddling together. You sense a deeper resonance coming through, common themes being explored. You think – and this is as important as anything else – of a title that makes things tick.

Good advice is hard to come by, but fresh perspectives (note the plural), might help you push to keep creating new material or re-think existing work.

All of this points towards a simple fact – creating a short story collection is also about growing up as a writer, reaching a maturity which enables you to fathom how stories hang together, the palette you work with, the themes which gnaw at you and how that is not such a ‘bad thing’.

And that’s about as much as I can tell you. For now.

About the author

About the author

KM Elkes is an author, journalist and travel writer. He has won the Fish Publishing flash prize, been shortlisted twice for the Bridport Prize and was one of the winners of the Aesthetica Creative Writing Award 2014. He also won the Prolitzer short story prize in 2014 and wrote a winning entry for the Labello Press International Short Story Prize 2015. His work has appeared in various anthologies and won prizes at Words With Jam, Momaya Review, Writing WM, Bath Short Story Award, Lightship Publishing and Accenti in Canada. He blogs at www.kmelkes.co.uk and tweets via @mysmalltales.

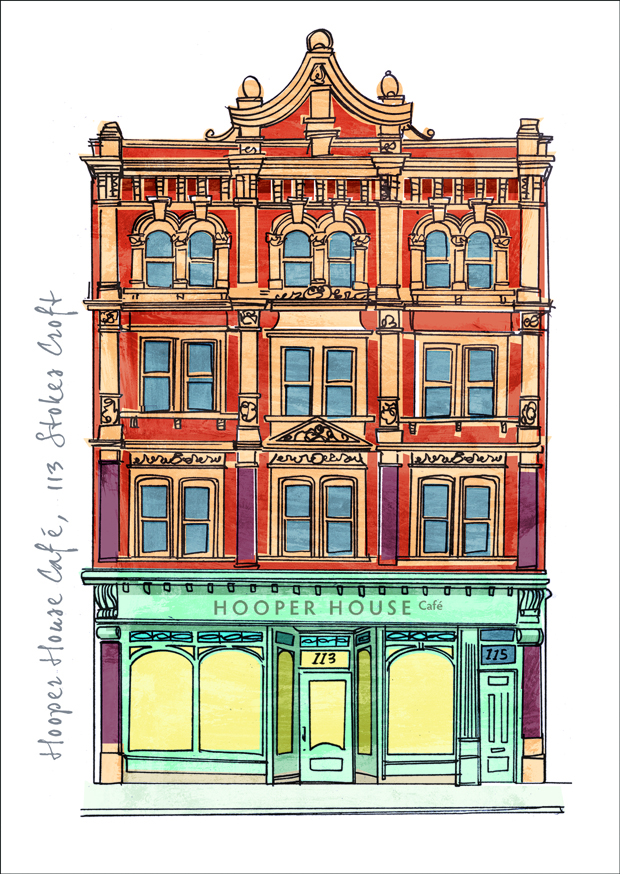

KM Elkes will be sharing more of his writing expertise at free flash fiction workshops taking place at Bristol Central Library for National Flash Fiction Day (this Saturday!), along with NFFD director Calum Kerr and prize-winning author KM Elkes. The workshops take place from 1.30-4.30pm. KM is also taking part in An Evening of Flash Fiction, from 6pm at Foyles Bookstore Bristol, along with a number of other writers, including Zoe Gilbert, Kevlin Henney, Sarah Hilary, Freya Morris, Grace Palmer, Jonathan Pinnock, and, well, me.

You’ve probably heard of Emma Donoghue’s extraordinarily successful novel Room. You may have seen the excellent screen adaptation, directed by Lenny Abrahamson and featuring Brie Larson as Ma and Jacob Tremblay as Jack.

You’ve probably heard of Emma Donoghue’s extraordinarily successful novel Room. You may have seen the excellent screen adaptation, directed by Lenny Abrahamson and featuring Brie Larson as Ma and Jacob Tremblay as Jack.