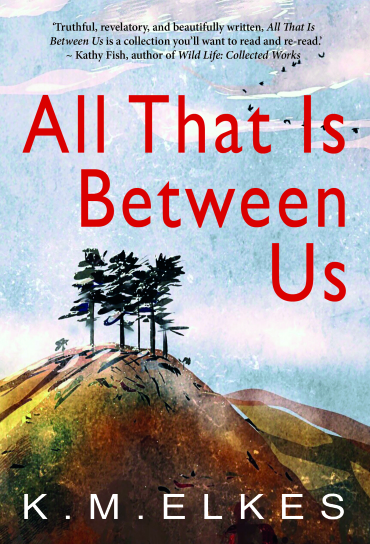

Warning: the intimacy in this book sneaks up on you, so that you’re living between the lines before you’ve had a chance to consider the implications – that if you do this, you’re going to empathise. You’re going to feel.

Warning: the intimacy in this book sneaks up on you, so that you’re living between the lines before you’ve had a chance to consider the implications – that if you do this, you’re going to empathise. You’re going to feel.

It’s a trait of K.M. Elkes’ writing that’s impossible to avoid. He draws you in with humour, and with exquisitely visual writing, until suddenly you realise you’ve become the character pressing their ear “against a window to feel the vibrations of trains and the deep, deep breath of the city”.

That’s a rare talent, most visible in this collection, perhaps, in You Wonder How They Sleep, in which the lines above appear.

Somehow, Elkes transports you, body and soul, less to another place than to another state of mind, into another’s state of mind.

In this collection, his debut (remarkably, it feels he should already have a shelf-ful of own-works), Elkes not so much invites you into other lives, as commandeers you: for the time it takes to read one of these brief flashes, or one and the next, and the next – as they’re addictive – you are immersed. You breathe the air his characters breathe, and ache exactly where they ache.

Elkes’ elegance with language is vivid throughout, frequently offering fresh terms on which to understand the world – “the buttery tang of trodden grass”, an old book with “the edges of its pages the colour of beer”, taxi cabs “yellow as a smoker’s finger.”

Picking a favourite story seems cruel, like choosing between a class-full of children, but inevitably one charmed me with its wit, its pathos and the ecological truth underpinning its fantasy. The King of Throwaway Islandis a love story in which the tale itself is being written by the protagonist repeatedly and released in plastic bottles from the island of refuse he’s been shipwrecked upon. “My island gets a little smaller ever time I send you a letter. But I stay confident – that’s part of the new me.”

In Swimming Lessons, an overbearing dad battles the ingrained hurt inflicted by his own father. Fathers crop up in many of the stories, often cruel, usually misguided, occasionally striving to do their best, and, at times, succeeding.

In Three Kids, Two Balloons, Elkes takes a passing moment and harnesses it in a way that somehow manages to be funny and moving and powerful. Hints of flippancy here, as in many of the stories, are deceptive, as beneath each is a bolt of such tenderness that you’ll be stopped in your tracks.

It’s intriguing that by fixing our focus firmly on the people at the heart of each tale, the stories themselves swell outwards, so that the details chosen to depict place and time become transferable across countries and, to an extent, eras. Loss is perhaps the most universally recognised emotion, and Elkes has the ability to make every situation he turns to infinitely relatable.

In that sense, the collection’s title rings with particular resonance – chiming with the awareness that in fact all that is between us are the things that make us human, which means that time, location and circumstance matter far less than our responses to the situations we find ourselves within.

All That Is Between Us by K. M. Elkes is published by Ad Hoc Fiction and is available to buy here.

Seen or read anything interesting recently? I’d love to know. I’m always happy to receive reviews of books, art, theatre and film. To submit or suggest a review, please send an email to judydarley(at)iCloud.com. Likewise, if you’ve published or produced something you’d like me to review, get in touch.

Lifetimes pass in a twinkling in this novella-in-flash from Diane Simmons. Eighteen tightly woven short stories sew together moving glimpses into the love, betrayals and reconciliations of four generations over a span of seventy years from 1932 to 2002.

Lifetimes pass in a twinkling in this novella-in-flash from Diane Simmons. Eighteen tightly woven short stories sew together moving glimpses into the love, betrayals and reconciliations of four generations over a span of seventy years from 1932 to 2002.

I have a stubborn streak that makes me shy from the books that hit mainstream esteem. Part of me wants to seek out the underdogs that will really benefit from the boost of a review. However, My Name Is Lucy Barton is the story of a woman whose childhood placed her squarely in the camp of underdog, with a level of poverty that Elizabeth Strout paints with visceral skill, rendering it utterly relatable without oiling the hinges with sentimentality.

I have a stubborn streak that makes me shy from the books that hit mainstream esteem. Part of me wants to seek out the underdogs that will really benefit from the boost of a review. However, My Name Is Lucy Barton is the story of a woman whose childhood placed her squarely in the camp of underdog, with a level of poverty that Elizabeth Strout paints with visceral skill, rendering it utterly relatable without oiling the hinges with sentimentality. Unexpected gems abound in

Unexpected gems abound in  Warning: the intimacy in this book sneaks up on you, so that you’re living between the lines before you’ve had a chance to consider the implications – that if you do this, you’re going to empathise. You’re going to feel.

Warning: the intimacy in this book sneaks up on you, so that you’re living between the lines before you’ve had a chance to consider the implications – that if you do this, you’re going to empathise. You’re going to feel. At the age of seven, Zettie stops speaking and concentrates instead on listening to the world.

At the age of seven, Zettie stops speaking and concentrates instead on listening to the world. The first anthology of novel excerpts from

The first anthology of novel excerpts from  In her debut short story collection

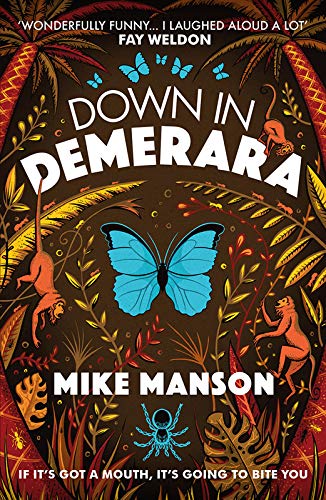

In her debut short story collection  Felix Radstock isn’t an instantly likeable protagonist. Fumbling his way through the unfamiliarity of Guyana, the best way to describe him might be as a tropical fungus – he’ll grow on you, whether you want him to or not.

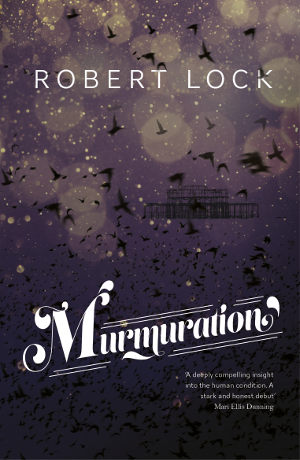

Felix Radstock isn’t an instantly likeable protagonist. Fumbling his way through the unfamiliarity of Guyana, the best way to describe him might be as a tropical fungus – he’ll grow on you, whether you want him to or not. Drawing us into the magic and squalor of a seaside town, Murmuration by Robert Lock is that rare thing, a novel strung from several stories, each of which contributes to the greater whole.

Drawing us into the magic and squalor of a seaside town, Murmuration by Robert Lock is that rare thing, a novel strung from several stories, each of which contributes to the greater whole.